- Home

- Warwick Deeping

The Woman at The Door

The Woman at The Door Read online

* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This ebook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the ebook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the ebook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a FP administrator before proceeding.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: The Woman at the Door

Date of first publication: 1937

Author: Warwick Deeping (1877-1950)

Date first posted: Oct. 8, 2018

Date last updated: Oct. 8, 2018

Faded Page eBook #20181013

This ebook was produced by: Mardi Desjardins, Al Haines, Jen Haines & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net

BOOKS BY THE SAME AUTHOR

* * *

Blind Man’s Year

No Hero—This

Sackcloth into Silk

Two in a Train

The Man on the White Horse

Seven Men Came Back

Two Black Sheep

Smith

Old Wine and New

The Road

Short Stories

Exiles

Roper’s Row

Old Pybus

Kitty

Doomsday

Sorrell and Son

Suvla John

Three Rooms

The Secret Sanctuary

Orchards

Lantern Lane

Second Youth

Countess Glika

Unrest

The Pride of Eve

The King Behind the King

The House of Spies

Sincerity

Fox Farm

Bess of the Woods

The Red Saint

The Slanderers

The Return of the Petticoat

A Woman’s War

Valour

Bertrand of Brittany

Uther and Igraine

The House of Adventure

The Prophetic Marriage

Apples of Gold

The Lame Englishman

Marriage by Conquest

Joan of the Tower

Martin Valliant

The Rust of Rome

The White Gate

The Seven Streams

Mad Barbara

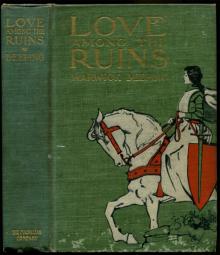

Love Among the Ruins

THE WOMAN AT

THE DOOR

By

WARWICK DEEPING

McCLELLAND & STEWART, LIMITED

Publishers Toronto

COPYRIGHT, CANADA, 1937

BY

McCLELLAND & STEWART, LIMITED

TORONTO

PRINTED IN CANADA

T. H. BEST PRINTING CO., LIMITED

TORONTO, ONT.

THE WOMAN AT THE DOOR

I

He first saw the tower when the larches were turning green. The heath, bearded with the bronze of last year’s bracken, and stippled with Scotch firs, rose suddenly toward the south. The skyline was spired with the green larch tops, and interspersed with the larches were old oaks and firs. It was one of those poignant days in April when the wind is in the south-west, and there is a whisper of spring in the air. Sunlight and shadows came and went. The flicker of sunlight on some bright surface was the first thing to catch Luce’s attention.

In this wild and solitary place he had supposed himself free of man and his bricks and mortar. There still were solitary places in Surrey. He had followed a lane in the deep valley where the soil was richer and beech trees grew. He had passed a farm, and beyond it the lane had died away in the hollow of an old quarry or sand pit, and Luce had taken to the heathland where ploughs had never turned the earth.

Glass,—sunlight on a window! But high up among the tree tops! And then he noticed a trackway less than a yard wide snaking its way amid the dry bracken and the heather. He followed the path, and as the network of winter boughs grew thin he saw, as through a kind of veil, a tall, grey tower.

Had he been a man of simpler reactions he might have greeted this ghost of a building with a “Well,—I’m damned!” Certainly, he stood and stared at it. Almost it suggested some mysterious exclamation-mark reared in brick and mortar by some whimsical madman. But why and when?—Somebody’s Folly? The Stylite’s Pillar of some recluse? That might not seem madness to a star-gazer and a dreamer of dreams, and John Luce was such a creature. He was conscious of a feeling of quickened heart-beats and of breathlessness, like a mystic who had discovered something strange in a world where strangeness is forbidden by bureaucrats and by-laws.

There was a little clearing here in the woods, an orchard full of old and shaggy trees, a weedy garden, all enclosed by a rotting wooden fence that was grey and green with lichen. A tangle of old laurels half hid the lower story of the tower. A great pear tree, nearly thirty feet high, was in full bloom, very white against the grey-blue glooms of the woods. But Luce’s eyes climbed up the ladder-windows of the tower. There were five of them, white-framed and white-sashed in a wall of grey stucco. In one place the stucco had fallen away to show the red brick beneath. The tower was an octagon, with an outjutting building attached to it like the nave to the tower of a church. It had a parapet, and a chimney stack with five red chimney-pots.

Luce counted those chimney-pots. Five flues, five stories, five rooms. And the view from the leads of the flat roof! It promised an immense survey of rolling wooded country, valley and downland. But what a retreat for a recluse who wished to dream, or write, or star-gaze! Nothing but tree tops and sky, and a window high up towards the sunset.

He became quite excited. Did anyone live here? Following the bank of laurels he came to a gate. A weedy path led to a flight of steps and a green door in a kind of porch that was attached to the base of the tower. Luce unslung his pack and hitched the straps over the gate-post. He went in, carrying his stick, for, as an amateur tramp he had come to know that an unexpected and angry dog might resent his curiosity.

The place appeared deserted. A light wind might be moving in the tree tops, but in this sheltered place the air was like deep water. The pear blossom was beginning to fall, and so still was the air that the petals fell straight from the tree. He could see no sign of human occupation. The garden had not been dug. There were clumps of daffodil in flower.

He tried the green door and found it locked. Circling the place he discovered a second door in the nave-like annexe, but that too was locked. The lowest window of the tower was some ten feet from the ground, and quite unreachable. How tantalizing! There was only one window that would satisfy his curiosity. It belonged to the lower story of the attached wing, and peering in he discovered nothing but emptiness.

Since there was no one to say him nay, Luce fetched his pack and took temporary possession of the orchard. He brought out a spirit-stove, and a kettle, a bottle of water, tea, sugar, a flask of milk, a couple of rock-cakes. Sitting on his empty pack, he waited for the kettle to boil, and allowed his fancy to play about the tower. He could suppose that it was more than a hundred years old, and that since its building the trees had grown up, and made it even more secret. But what strange whim had set it here in the middle of a roadless heath?

He had just lit his pipe when the inspiration shaped in him. What a retreat for a recluse! What a place to work in!

Often he had played with the idea of building himself some such retreat in the middle of a wood. As a social creature he was essentially eccentric, a fourth di

mensional mystic with a private income of eight hundred pounds a year. He was forty-five years old. Three years ago he had lost his wife, and since her death the mechanism of modern life had become even more unreal.

Peace!

Like Falkland he was crying: “Peace, peace” in a world that was growing more and more crowded and complex, a world that knew nothing of the John Luce who had produced a strange and fantastic book entitled “The Mathematician and the Mystic.” Just ninety-three copies of the book had been sold, and of the ninety-three perhaps a baker’s dozen had been read from cover to cover.

But, by the time he had finished his pipe the whim had taken shape in him and become so definite a purpose that it changed his plan. He had been tramping for three days, and this was to have been the last of them, for he had proposed to pick up a train at one of the valley stations and sleep in his Bloomsbury flat. He pulled a map from his pocket, spread it on the orchard grass, and lay prone, studying it.—Brandon Heath. Yes, if he bore south-east he would strike a road leading to West Brandon village. Good. West Brandon it should be. With his pack once more on his back, and his stick in his hand, he stood under the pear tree and contemplated the tower.

It tempted him. He was conscious of a strange passion to possess it.

2

Tramping under the beech trees into West Brandon he came to the village’s one responsible inn, The Chequers. West Brandon still smelt of the eighteenth century, and was beautiful, a village of individual cottages set back from the road in gardens. Rooks were busy in the high elms beyond the church. Orchards were in flower. One old red house raised its gables and chimneys amid the gloom of cedars. Of shops there were perhaps three, but West Brandon was feeling the urge of modernity. It had taken to itself a garage, and an estate office, for the inevitable syndicate had acquired building land here.

West Brandon did not trouble to stare at Luce. He was just a large person in an old plus-four suit, hatless, going grey at the temples, and with a pack on his back. The Chequers, a white building, set back from the road behind posts and chains, accepted the gentleman with a casualness that was not intended to be churlish.

“Can I have a room for the night?”

The sophisticated young person in the office gave him a cursory glance. He was just one of those earnest, middle-aged asses who walk about the country looking at churches and exploring by-ways, which, to the sophisticated young person is, in an age of wheels, mere foolishness.

“One night?”

“I might stay two.”

The young person was looking through some new gramophone records.

“No. 3. Dinner’s at half-past seven.”

She did not offer to direct him, and Luce made his way upstairs in search of No. 3. He wanted a bath. He found both Room No. 3 and an elderly maid sitting by a landing window mending someone’s socks.

“Can I have a bath, please?”

He was a somewhat shaggy person both as to hair and clothes, but the maid was less inhumanly self-centred than the young person below. She knew a gentleman when that rather rare genus put in an appearance, and this gentleman had a peculiarly gentle face. Yes, the dreamy sort who painted pictures or took photographs and scribbled in little books. The maid put her mending aside and stood up.

“Yes, sir.”

Luce strode into No. 3. He was a very big man, and like many very gentle creatures, extremely powerful. The floorboards of No. 3 complained of his weight. The maid heard him moving about in the room, softly whistling some song that was strange to her. As a tribute to his type she had given the bath a wipe, and put down a clean pink bath-mat. She knocked at his door.

“The bath’s ready, sir.”

He appeared in a blue shirt, brown knickers and stockings, with a sponge-bag looking puny in a large hand. The maid had returned to a chair by the window. From it you could see the high elms beyond the church, and hear the rooks’ chorus.

Luce paused on the landing.

“By the way, do you happen to know this neighbourhood?”

Her rather tired blue eyes met his. She was sufficiently old to be wise as to when a particular gentleman could be humoured.

“I was born here, sir.”

“Been here all your life?”

She gave a little wincing smile. No; she had other memories than those associated with West Brandon, but they had not been happy ones.

“Not quite, sir.”

“Do you happen to know Brandon Heath?”

Did she not? As a girl she had walked with a lad on Brandon Heath.

“There’s a queer place there, a tower.”

“O, you mean the old signal tower, sir.”

“Signal tower?”

“Yes, sir, in the old days they used to telegraph from it. They do say there were towers all the way to Portsmouth.”

Luce’s face was suddenly illumined.

“Of course. A semaphore tower. Why didn’t I think of that? Thanks, very much,” and he went in to his bath.

The maid heard him splashing and humming a tune. Yes, this was a nice gentleman, the sort of man who would have made a woman a good husband. And he hadn’t. Or—had he? He looked the bachelor sort, easy and absent-minded and natural. The maid let the sock lie in her lap and stared with faded eyes at the elm trees. It was spring and the rooks were busy, and all April things had gone out of her life. And suddenly her face looked old and haggard.

The bathroom door opened, and he was there in the same blue shirt and shaggy brown knickers and stockings. His hair looked wet, his face at peace with the world. She noticed how very blue his eyes were.

“By the way—do you happen to know who owns that tower?”

“I think it belongs to the Brandon Estate, sir.”

“And who?”

“O, Sir Evelyn Gage.—But he’s always abroad, sir. Mr. Temperley could tell you.”

“And who is Mr. Temperley?”

“The agent, sir. He’s a lawyer, too. Lives in the old red house at the top of the village.”

Luce thanked her, and disappeared into No. 3. He had decided to call on Mr. Temperley.

3

Mr. Temperley, who was seventy-three years old, had lived so long and so intelligently, and through so many transformations that nothing surprised him. Mr. Temperley just chuckled. He had a fine head of white hair, and a skin that many a woman of five-and-thirty might envy. In fact, he was a handsome, stately and jocund old gentleman, with nothing dusty or documental about him.

Mr. Temperley had dined and was reading The Times in his library when a maid came in with a card on a salver.

“A gentleman from the Chequers, sir, wants to know whether you could give him an appointment for to-morrow morning.”

“What sort of a gentleman, Mary?”

“In knickerbockers, sir, and without a hat.”

Mr. Temperley chuckled, picked up the card and read it.

Obviously, a cultivated person both as to clothes and club, for in these days the gent le world went shabby. Mr. Temperley liked his glass of port and his dash of colour. He wore it in his tie, a gay cerise, also a black velvet coat in the evening. But, Mr. Temperley, being seventy-three, did not temporize with life; the little that was left of it he liked brisk and bracing. He was completely frank in his philosophy—“It’s a good world, even at seventy-three.—I’m not clamouring for my coffin.”

“Show the gentleman in, Mary. I’ll see him now.”

These two men had not been together for more than a minute when they were perfectly at ease with each other. Luce, offered a glass of port, refused it gently, but asked to be allowed to smoke a pipe. They had their feet to the fire. Luce, filling a pipe, confessed that he considered it very courteous and kind of Mr. Temperley to admit a perfect stranger into his house at such an hour, and on business. Mr. Temperley twinkled bright eyes at him, and also filled a pipe. Not at all. Mr. Temperley’s interest in life was almost that of a vigorous child. The unexpected was ever the most piquing.—And what, exact

ly was Mr. Luce’s business?

Luce looked at the fire, a wood fire piled against an old fireback.

“Too hot for you, Mr. Luce?”

“No.”

“November likes its fire—even in April. Well——?”

He lit a paper spill at the fire, and held it to the bowl of his pipe.

“I understand that you can tell me about the old signal tower on Brandon Heath.”

“The signal tower?”

“Yes, I stumbled on it this afternoon. . . . A unique sort of place. I confess it gave me a thrill.”

Mr. Temperley gave him a quick, birdlike look. He might be seventy-three, but he understood that sort of thrill. As a Surrey worthy, and one of its shrewdest archæologists, he could grow excited over a piece of flint, or the vague swell of an old vallum. O, yes, he could give Mr. Luce the information he desired. According to the records there had been eight such stations between Whitehall and Portsmouth. They had been built as naval signal stations in 1795. Each had been staffed by a lieutenant, a midshipman, and two sailors. The stations? Yes, Putney Heath, Brandon, Netley, Hascombe, Blackdown, Beacon Hill, Portsdown. Mr. Temperley was of the opinion that not all the stations had been towered. It had depended on the natural altitude of the site. And was Mr. Luce writing a book on the subject?

Luce smiled at the fire.

“No. I do write books—occasionally. And the Brandon tower is empty?”

Mr. Temperley crinkled up his eyes.

“Yes. We let it off to a fellow named Ballard, a farmer. One of his labourers and his family lived there. But we had a difference of opinion with Ballard. He had a yearly lease, and we did not renew.”

“So, the place is habitable?”

“In a sense,—yes.”

“Would you let it or sell it?”

Mr. Temperley drew in his legs and sat up in his chair.

“To you?”

“Yes.”

“But,—my dear sir!”

And then after contemplating for a moment his visitor’s frank and tranquil face, he began to divine the pleasant unusualness of Luce and his whimsies.

The Woman at The Door

The Woman at The Door Apples of Gold

Apples of Gold The Seven Streams

The Seven Streams Old Wine and New

Old Wine and New No Hero-This

No Hero-This Two in a Train

Two in a Train Valour

Valour Shabby Summer

Shabby Summer Love Among the Ruins

Love Among the Ruins The Short Stories of Warwick Deeping

The Short Stories of Warwick Deeping